tv George Will on Religion Politics CSPAN December 30, 2012 1:40am-3:10am EST

1:40 am

susan rice, possibly secretary of state, having holdings in the companies that are gonna build that pipeline. >> yeah. it's amazing. as i said, i thought that it's so obvious that we couldn't be so stupid as to develop the unconventional fossil fuels because they're dirtier, you get less energy per unit carbon and you get all these other pollution, regional pollution. so we need to try to talk common sense into them and we've -- you know, we've done -- i've been arrested in the front of the white house because of the tar sands. and there are more and more people who are willing to stand up and protest against those. and i know i sound like a broken record, but just -- and i've realized that just trying to block an individual carbon source, although that's meritorious, it won't work if we don't have a price on carbon. >> yeah. and china will just -- all right. we're gonna invite your participation and, particularly, if you haven't had

1:41 am

a chance to ask a question. and i'm gonna be assertive about -- i'm encouraging you to be brief and get to your question so we can get as many people to participate as possible. the line starts with our producer jane ann right there, and then i welcome your comments for dr. hansen. let's invite the audience participation. yes, welcome to climate one. >> thank you. congratulations. you deserve this award and thank you to all the scientists who are here who are providing we, policy makers and activists, with the information we need. i'm holly kaufman. my question is, in addition to the price on carbon, for some shorter term measures, what is your opinion on dealing with some of the shorter term but higher global warming potential gases like methane, which might not be as politically controversial to deal with? >> yes.

1:42 am

i think methane and black carbon and some of the trace gases are -- it's important that we deal with those and they may be the way on which we can handle the faustian bargain. because as the sulfate aerosols decrease, we've got to try to find a different way to reduce the climate forcing the energy imbalance, that is caused by removing the sulfate. so i think those are important, but i -- the priority has to be on co2 on the -- because of the fact that if we continue on this path with co2, we'll get to a point where it's really consequences are too great and very difficult and are impossible for our children to deal with without having great disaster.

1:43 am

so i think that they're important, and i just don't talk about them as much as i used to because it's kind of distracting from the main problem which is the fossil fuel, co2. >> yes, welcome to climate one. thank you. >> hi. if we were to do something like pyrolize sewage, garbage and agricultural waste, what's the potential for that to remove carbon from the atmosphere, how fast might it be possible to do that? >> yeah, we've looked at so- called biochar. biochar, in many -- not everywhere, but in some agricultural systems, it can be very beneficial for improving the productivity of the soil. and so, that is a one way that we can get some of that excess co2 out of the atmosphere. and it's, you know, i'm looking at the numbers, it doesn't look

1:44 am

huge and it -- but it's -- and it's uncertain how big it can be. and it's one thing that we should be researching in our agricultural schools, because it is potentially very helpful. >> so the next question for dr. hansen, yes. >> yes, john addison, clean fleet report. a price on carbon would of course encourage energy efficiency, fuel efficiency. where are you seeing progress there? where do you think are some of the most effective mechanisms? >> technologically, for -- well, the biggest -- the quickest thing -- our energy efficiency in the u.s. isn't -- is not very good. and we've run economic models which suggest that if we put a $10 a ton tax on carbon, increasing $10 a ton per year,

1:45 am

so that after 10 years, it's equivalent to a dollar a gallon on gasoline. that that would reduce carbon emissions in the us by 30%. which is about 11 times -- that 30% reduction is 11 times greater than the amount of carbon carried by this keystone xl pipeline. so it just shows how foolish that pipeline is, compared to the kind of steps that we should really be taking to ensure our energy independence. but the -- there are multiple ways that price would affect -- would reduce emissions. but, yeah, i -- and i don't really know that i should or

1:46 am

could actually specify what -- which technology is gonna do. as i say, the marketplace is going to make those decisions. but there's a lot of potential already, well california is twice as efficient as the rest of the nation. it's about equivalent to europe, which is also twice as efficient as the united states. so there's a lot of potential in just energy efficiency but anyway. >> and so the next question, welcome. >> i'm james. the ongoing talks in doha, basically focusing on kyoto, i believe, you've said you sort of have issue with kyoto, what do you think the united states should be putting forward there, and how can we convince the countries who have equity issues with the united states and our carbon development to participate? what do you propose for that? >> the united nations process hasn't done a lot. what do you think should happen there? >> yeah, it's -- they -- as i've already said, i think

1:47 am

instead of trying to fix the kyoto process but keeping the cap-and-trade system, we need to realize that we have to put a price on carbon. now, we do have a debt to developing countries because the climate impacts are actually going to be felt and are already beginning to be felt more at the low latitude countries where more of the developing nations are, and yet, they have not contributed at all or very, very little to that carbon in the atmosphere. so we're gonna have to figure out some compensation for them, and it actually takes not very much money to encourage them to

1:48 am

have better practices and to restore for us or to preserve for us, for example. so that's -- that needs to be part of the process. but we need to -- you know, when i was in the netherlands, a week or two ago, we met a man, who had -- that had this lamp that's all powered by solar. so it has a solar panel which can charge up in the daytime. even on a cloudy day, it would charge up, and it will provide light for up to eight hours. it has different strengths depending on how bright you use it. but he was -- and he wants to -- this to be -- replace kerosene lamps.

1:49 am

and i know about kerosene lamps. i was born on a farm that did not have electricity, and we used kerosene lamps. and my four older sisters all did their homework -- after it gets dark, that's what provided the light. and they did their homework and coloring and things with these lamps, and, of course, my parents were in fear of them tipping one of these things over and burning down the house. it turns out that there are 15,000 serious burns per day from kerosene lamps in the developing world, and there are 800 million women and children who are breathing the equivalent of two packs of cigarettes per day from the fumes from kerosene lamps.

1:50 am

and yet, you -- with one of -- this little lamp can be -- it has a cost of $9 to $10, and they're spending 30 cents a day on kerosene. so this thing could -- can replace the kerosene lamp with about a month's worth of kerosene can replace -- so we -- so a developing world -- anyway, what i'm saying is, there are a lot of ways that we can -- the developing world can jump over technologies and not make the mistakes that we did. and we have to help them do that; that's part of our debt to them. we should be making an effort to do those sort of things. >> i think secretary clinton is a big supporter of those solar cook stoves and those other things to do that at a reasonable cost. let's have our next question. yes. >> yeah. i'm warren linney from kiara solar. and i just want to thank you for your courage. i've been arrested a few times for these issues as well. it's worth it. my question is, i wanna know if

1:51 am

you're aware of any council of engineers and scientists that are evaluating and prioritizing the various low carbon technologies, and also the ones that maybe will pull out enough carbon from the air and--like carbon engineering, global thermostat, in order to have a priority of funding these, and do you know of any fund that's being ready to, you know, save life on the planet as well. >> well, you see, those studies are academic. you know, so we had this nice paper, one called wedges, which said, you know, we can -- there's this wedge that could reduce our carbon 10% or 5% and there's this wedge should do five more and then there's this wedge five more. so they list a whole bunch of technologies that might reduce the carbon emissions. in principle, they could do that. and then, actually, when you talk to the authors, they say,

1:52 am

we're -- are there any more wedges? they say, oh yeah, there are a lot more wedges. at least we got tired. -- we just got tired. you know. so -- but those things were theoretical. what will cause those in reality, you put a price on carbon, some of those wedges would really be great stuff and they would -- you'd pass a tipping point that would really take a big chunk of the energy. and some of them wouldn't work out at all. but, you know, you just can't do it with theoretical exercises. the way that it will work -- sorry, it's a broken record, but you got to have a price on carbon. >> and so -- [laughter] >> right. but you talk about the marketplace. one of the ways that u.s. has reduced its emissions is through switching from coal to gas, and that was government innovation 30 years ago developing some tracking technology that no one saw a few years ago, and -- that proponents would say that that switch is a good thing, it's reduced carbon emissions more than kyoto or anything else has

1:53 am

been technology innovation and markets. >> there are two different things though. the gas -- yes, if gas were treated as the transition fuel allowing us to leave the coal in the ground and be working on the successor to gas so that that's all we burn, then we could actually meet the targets. but that's not what's happening its exactly -- they're actually going after every fuel they can find. it's fracking -- in addition to tar sands, in addition to drilling in the arctic, in addition to mountain top removal, and in addition to tar shale, that's why they say, united states is gonna be the saudi arabia of oil. how is that? we're gonna cook the rockey mountains and drip oil out the bottom. and that's gonna be -- that's almost -- it's 50% more energy to get that oil out. we -- and the fracking, we can't do that. there's so much gas if we insist on finding ways.

1:54 am

it's actually very expensive and energy intensive to do that, but because we're subsidizing it, they're able to get away with that and -- >> and it's also happening in california in a big way. >> well, that's the problem. and there's only thing that will stop that. [laughter] >> all right. and so far, we got six minutes left. let's try to get a couple of questions in and quick questions, quick answers. yes sir, welcome to climate one. >> well, thanks a lot for your book. as you said, the issue is very complex. so is there an organization which will train citizens like me on how to explain this issue to my network? >> yeah, that's what i've been told. i thought that i was writing a book that would allow people to understand this. and i guess some people that -- even college-educated people said they have to read it twice, and so it's not -- they

1:55 am

say it's too technical. so we need clearer -- maybe mike's book because i haven't read it yet, but -- >> but your -- but your next book is gonna be letters to your granddaughter. >> yeah, my next book is gonna be sophie's planet. and sophie is helping me. i'm writing her letters and making sure they're understandable to her. >> and sophie is a teenager? >> sophie is now 14. she's my oldest grandchild. and i'm gonna try to make this understandable, more understandable. >> i'm sure she's smart. let's have our next question. yes, sir, welcome. >> yeah, hi. i'm nils michael langenborg from sustainable adam smith. congratulations from the award. so adam smith wrote about -- he said consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production. so if consumption is really the issue here, how do we get all -- how do we get everyday americans to modify their consumption, and how do we get policy makers like governor brown who's sitting in the room

1:56 am

here, spoiler alert, and what is his position on this, i would be more than happy to hear. so how do we get people to be -- to change their behavior? and, secondarily, how we make this fun because this is such an intense topic, when you walk out of here and all you wanna do is -- >> drink. okay, so -- >> drink. [laughter] >> well, we can work -- we have some wine outside afterwards. a quick question. we got a few minutes left, so consumption -- >> yeah, consumption. well, that -- again, the carbon price will help with that, to make things -- but and that is an education thing. we need to get our children and grandchildren and the public to appreciate nature and things, not just more things. but that's a -- that's part of the problem, so -- and putting a price on it will help a bit.

1:57 am

>> welcome to climate one. yes, we're getting toward the end. thank you. >> it's an honest pleasure to be here with you. and before i came up, i was gonna ask you what's it like being around your christmas or thanksgiving table, talking among your family, when you get to talk about your passion, because i don't think that you actually talk climate science 26 hours a day. but could you tell us a little bit of your conversations with sophie? thank you. >> yeah. so i don't think that it's appropriate to frighten children. [laughter]. and i -- so the only thing that -- until -- now, sophie is -- i have five grandchildren, sophie is the oldest, and finally, i am starting to explain the problem and the fact that there are solutions. but, other than that, i just -- the only thing that i've really done with grandchildren related to this is to try to help them

1:58 am

understand nature. so for -- in particular, as i mentioned in my book, we have addressed the monarch butterfly problem. you know, a monarch butterfly as we've noticed on our farm, they are many fewer than they used to be, and that's mainly because not of global warming, but because of pesticides which have been used to reduce the number of milkweeds. and that -- so, therefore, with my grandchildren, we plant milkweeds. and then they learn about this remarkable life cycle of monarch butterflies which migrate all the way to mexico. well, i did -- i actually put one of my letters to sophie on my website. and i -- and it was worked out very nicely because i then got a letter, i got an email from a scientist in mexico. these monarch butterflies

1:59 am

migrate all the way from canada to this mountain in mexico where they hibernate for the winter on a one small region. and this mexican scientist is -- realized that these trees where the butterflies are hibernating, they're not doing well. the tops of the trees are turning brown because of their -- they've had multiple droughts. and the -- and that was one of the things i wanted to get to in my book and explain it to sophie, that the danger to species is the shifting of climate zones. if we go with too large of climate change, that rapid shifting of climate zones is going to put additional pressure on species and cause many of them to go extinct, and then because they're interdependent, ecosystems can collapse. well, this scientist was trying to convince the mexican

2:00 am

government to plant these seedlings higher up the mountains because it's getting warmer, and for those trees to exist, they need to be in a cooler -- and -- but then he figured, he looked at ipcc, this intergovernmental panel, the climate change reportrealize mountain will not work. then you have to try to plant those trees on a different mountain and convince those monarch butterflies, which have been programmed, they have to go to a different place. we have tried to do that with some species, the whooping crane, which is one that i know about because it almost went extinct. but anyway -- but they tried to guide that whooping crane to a different place, so that it's not in danger -- it's not in so much danger of having only one place where it can winter. but anyway, the point was -- what was the question? [laughter] >> it was getting out of -- we got a chance for one last quick question, one quick answer. we're out of time.

2:01 am

we got to present the award. yes, sir. >> yeah. okay. a very quick question. have you -- >> i don't know what your question was but the answer was good. okay. [laughter] >> hi, my name is gerald harris. i specialize in scenario planning in the energy industry. but you're the first scientist i've heard say something positive about sequestration of carbon. and as i understand it, there is no way that we can store it without a risk of a catastrophic release. so maybe you know something that i don't know about this but is there any way we can actually store sequestered carbon without a risk of a catastrophic release? >> well, i think that there are ways, but it's going to be a case of many -- you don't want it in your backyard. it's very possibly the case. and, you know, we've done so much oil drilling -- drilling looking for oil that this -- that is not clear that most of the continental sites are safe. but there are places you could put it offshore where you're putting it at a depth where just the pressure and

2:02 am

temperature are such that you don't have to worry about it coming out. so it is possible, but it's gonna cost money. so you have to let it -- let that technology compete against energy efficiency and other forms of energy. >> and we got to wrap it up there. thanks to james hansen, head of nasa goddard institute for space studies, adjunct professor at columbia university's earth institute for his comments here today at climate one. [applause] >> okay. i'd like to -- thank you very much. i'd like to invite ben santer up here to present the award to dr. hansen. ben is a member of the jury and a climate scientist in his own right at lawrence livermore lab.

2:03 am

>> jim, you and steve were pioneers of the frontiers of climate science, exploring the role of the oceans in climate change, the role of clouds, the role of aerosol particles, and i could spend a lot of time recounting your scientific contributions. i won't -- i just wanna tell you one very brief story. back in 1988, i was doing my postdoc in hamburg, you testified in front of congress. you said, we see the signal emerging from the noise. that had huge influence on me and on hundreds, thousands of my colleagues. the idea that we could see some coherent human-caused warming signal emerging from the year- to-year or decade-to-decade noise of natural climate variability, it certainly had a discernable influence on my career and on the science i chose to do. germans have a word, zivilcourage, there's not really an english translation for it.

2:04 am

and what it means as best as i can translate it is, individuals who show extraordinary courage, not in the extraordinary circumstances of war, but in the extraordinary circumstances of our day-to-day lives. for me you embodied zivilcourage. you've shown not only through your science, but also through your defense of the science, through your congressional testimony, through the work that you've done in the last few years telling the world that we don't have the luxury of remaining silent anymore. we have to go and speak truth to power, to tell people, this is where the chips are lying. this is what the science tells us. it's a real honor and a privilege to, on behalf of the jury, on behalf of bud ward, larry goulder and greg dalton, present you with the 2012 steve

2:05 am

schneider climate science communication award. as you know, steve had the metaphor about cloudy crystal ball -- [laughter] -- hold this up -- getting across the idea thsat we can't precisely see the details of what's in the pipeline as you put it, the shape of things to come for the climate system, but we know enough. we can see clearly enough. thank you for everything that you've done. it's a real privilege to call you a friend and a colleague. [applause] >> and we've been talking -- today, we've been talking about courageous communication and climate communication.

2:06 am

a lot of politicians have walked away from this issue with a few exceptions; governor huntsman is one, governor jerry brown of california. it is another -- and i'd like to invite governor jerry brown to come up here and say a few words. [applause] >> thank you, no it's all right. i just wanted to say congratulations. you went out in the forefront, doing great science with good public policy. so on behalf of california, we are also on the forefront. as we just heard, the forefront isn't good enough, [laughter] but it's still pretty damn good. so, anyway, keep on doing what you're doing -- >> yes, sir. >> we've got a lot of work to do from the idea to the execution into the politics, it's -- a lot of gaps there, and you're hoping to close in and i

2:07 am

just want to thank you for it. >> thanks very much. [applause] >> thank you very much. >> may i? >> sure. >> okay. do i need this? >> i think you have your own. >> okay. yeah, just one more comment about -- as i mentioned, steve schneider was a friend from many decades ago. tell you one more thing about him. in his first year as a postdoc, he was -- steve was very outgoing and very -- already, at that time, he was trying to reach to the public. and he wrote a letter to the editor of new york times. and, at that time, the director of the goddard institute did not appreciate that sort of thing. [laughter]

2:08 am

he called a meeting of entire people in the building, you know, more than 100 people coming to -- and he really gave it to steve. and the great -- and the really impressive thing about steve was, you know, he didn't back down. so he -- even at that time, when he's just as around 26 or 27-year-old postdoc, he had the courage to stand up for what he believed in. so he was really a good example of courage of a scientist at a very early age. [applause] so anyway, it's -- for all those things about steve, it is a great honor to get an award in his name. thanks. [applause]

2:09 am

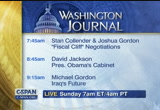

>> coming up, george will talks about the relationship between religion and u.s. politics and then a hearing on terrorist abuse of refugee programs. >> tomorrow, we will talk about the latest on the so-called fiscal cliff with the joshua gordon of the concord coalition. that is followed by a look of president obama's second term. our guest is david jackson. and then what is next for iraq. we're joined by author michael gordon. live at 7:00 eastern on c-span. >> they started to get worried in 1774. the british diplomats were

2:10 am

reporting to the crown that the colonists were sending ships and trying to get ammunition and cannons. this was after the british had sent more troops after the boston tea party. it is clear they were pulling together ammunition. maybe they did not intend to use it. that was a debate. the kings basically prohibited british ships from taking ammunition and everything to the colonies, unless it was officially sanctioned. they were very alert to this. as soon as the colony's a found out about it, in new hampshire and then rhode island, the militia took over and took the

2:11 am

ammunition, so everybody knew it was coming. >> he suggests that 1775 was the critical launching point of the revolutionary war and american independence. sunday night at 8:00 on c-span's q&a. author an analyst george will talks about the relationship between religion and american politics. he is introduced by john danforth. from washington university, this is an hour and a half. >> finally, it is my honor to introduce senator john danforth, who will introduce mr. will. the senator is a partner with the law firm. he graduated with honors from princeton university, where he majored in religion.

2:12 am

he received a bachelor of divinity degree from yale divinity school and a bachelor of laws degree from yale law school. he practiced law for some years and began his political career in 1968 when he was elected attorney general of missouri in his first place for public office. missouri voters elected him to the u.s. senate in 1976. they reelected him in 1982 and 1988, for a total of 18 years of service. the senator initiated major legislation in international trade, telecommunications, health care, research and development, transportation, and civil rights. he was later appointed special counsel by janet reno.

2:13 am

he later represented the united states as u.s. ambassador to the united nations and served as a special envoy to sudan. he has been a great friend to missouri, st. louis, and washington university. please join me in welcoming him now. [applause] >> thank you. thank you very much. i owe our speaker an apology. when you hear the apology, you are going to conclude that i am a really terrible human being. i am the kind of person who takes advantage of a friend, especially a friend who is vulnerable. when he is vulnerable, i pounce.

2:14 am

tonight's origin was a rehearsal dinner the night before the wedding of victoria will, george's only daughter. george was standing on the edge of the hotel ballroom taking and one of life's great moments. the marriage of the daughter is so deeply emotional. george the loving father was clearly caught up in a moment. that was the moment i seized the opportunity to strike. i sidled up to him and whispered ever so softly in his ear, would you mind giving a

2:15 am

lecture at washington university? you might ask how anybody could have been so insensitive. after 18 years in the senate, it came naturally. [laughter] george has been a close friend for nearly four decades and it is wonderful to welcome him to st. louis, even if the invitation so disgraceful. george will is one of the most recognizable people in america today. certainly, the most widely known intellectual. he is the author of the least a dozen books. since the early days of the show, he has been a regular on what is now "this week with george stephanopoulos."

2:16 am

2:17 am

perfectly acceptable. my dear friend william f. buckley once called up his friend charleton heston, the actor, and said chuck, do you believe in free speech? he said, of course. he said good, you are about to give one. it is a delight to be back here. it is a delight to be back on campus. long ago and far away, i was a college professor. in 1976, two of my friends ran for the senate against each other in new york state. the night they were both

2:18 am

nominated, jim buckley got up and said, i look forward to running against professor moynihan. i am sure he will conduct the high-level campaign you expect of a harvard professor. jim buckley is referring to you as professor moynihan. pat said, the mudslinging has begun. [laughter] what you are in for tonight, however, it is a lecture on political philosophy. take notes, there will be a test.

2:19 am

in 1953, the year in which the words "under god" were added to hee pledge of allegiance, it proclaimed the fourth of july and national day of prayer. on that day, eisenhower fished in the morning, golfed in the afternoon, and played bridge in the evening. there were prayers -- perhaps when the chief executive faced a daunting putt. this was not his first foray into the darkened ground of the relationship between religion and american politics. three days before christmas in 1952, president elect ike made a speech in which he said "our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in the deeply felt religious faith and

2:20 am

i do not care what it is." he received a much ridicule from his cultured despise years. his professed indifference to the major of the religious faith. it is the first part of the statement that deserves continuing attention. certainly many americans, perhaps the majority of them, agreed that democracy or at least our democracy, which is based on a belief in natural rights, presupposes religious faith. people believe this that all people are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights. there are two separate propositions that are pertinent

2:21 am

to any consideration of the role of religion in american politics. one is an empirical question. is it a fact that the success of a democracy requires a religious people governing themselves by religious norms? the second question is a question of logic. does belief in america as distinctive and democracy, a limited government whose limits are defined by the natural rights of the government, do those entail religious beliefs? regarding the empirical question, i believe religion can still be supremely important and helpful to the flourishing of our democracy.

2:22 am

i do not believe it is necessary for good citizenship. regarding the question of our government's logic, i do not think the idea of natural rights requires a religious foundation or even that the founders uniformly thought so. it is, however, the case that natural rights are especially grounded when there are grounded in religious. we in journalism are admonished not to bury the lead. we are supposed to put the most important point early on in our story. i will begin by postulating the following. in the 20th-century, the most important decision taken anywhere by anyone about anything was the decision made in the first decade of the last century about where to locate princeton university's graduate

2:23 am

college. princeton's president, a starchy presbyterian named woodrow wilson, wanted the graduate college located on the main campus. he wanted students to mingle. wilson's adversary wanted the graduate college located where it now is. woodrow wilson was a man of unbending temperament when he was certain he was right, which was almost always. he took his defeat about the graduate college badly. he resigned the presidency, went into politics. ruined the 20th century.

2:24 am

[laughter] i simplify somewhat and exaggerate a bit. i do so to make a point, however. to date and for the past century, since woodrow wilson was elected the nation's president 100 years ago, american politics has been a struggle to determine which best understood what american politics should be. should we practice the politics of woodrow wilson? or the politics of james madison? 1771. what has this to do with our topic today, the role of something ancient, religion, in something very modern, american politics? the crux of the difference between the approaches to politics is the concept of natural rights. as i draw for you my picture of

2:25 am

the rivalry, i recall the story of a teacher who asked her class to draw a picture of whatever here she chose. she circulated among their desks. pausing at the desk of little sally, she asked, of what are you drawing a picture? i am drawing a picture of god. the teacher said, no one knows what god looks like. sally replied, they will in a minute. [laughter] in 30 minutes or so, you will have the picture or so of my theory of the role of religion in american politics. i will note three peculiarities. i write about politics to support my baseball habit.

2:26 am

jack had the bad taste to mention the chicago cubs. i grew up midway between chicago and st. louis. i had to choose between being a cubs fan and the cardinals fan. all of my friends became cardinal fans and grew up cheerful and liberal. [laughter] i became a gloomy conservative, but not gloomy about long-term prospects.

2:27 am

america has just had a presidential election, its 57th. the ticket of one of the major parties did not contain a protestant. this was an event without precedent. it is especially interesting because the ticket, a mormon and a catholic, was put forward by a party -- regarding religion, the times, they are changing. when are they not? i am part of this interesting change. i am a member of the nones. not n-u-n-s, n-o-n-e-s.

2:28 am

when americans are asked their religious affiliation, 20% say none. my subject is the role of religion and politics. i am not a person of faith. concerning this, permit me a few digressions. i am the son of a professor of philosophy. he was the son of a lutheran minister. my father may have become a philosopher because his father was a minister. as a boy, the future professor will sat outside the pastors study door listening to the pastor and members of his congregation wrestle with the problem of reconciling free will. by the time my father became an

2:29 am

adult, after a childhood of two or more church services every sunday, he had seen quite enough of the inside of churches. he also had acquired a philosopher's disposition. i was raised in a secular home, but one which the table talk often took a reflective turn. my father had recently so adjourned at oxford, i was able to spend two years there. oxford was the vibrant center of the study of philosophy. because of that, i next went to princeton to study political philosophy. i began in journalism at the national review. religion is central to the

2:30 am

american party because religion is not central to american politics. religion plays a large role in nurturing of the virtue because of the modernity of america. our nation assigns the politics, encouraging the flourishing of the infrastructure of the institution that have the primary responsibility for

2:31 am

nurturing the sociology of virtue. these institutions with their primary responsibility are of the private sector of life. they are not political institutions. some of our founders, notably benjamin franklin, subscribe to the 18th century, a creator that wound up the universe like a clock and did not intervene in the human story. the diest god is like a rich aunt in austrailia. deism explains the existence of the nature of universe, but so does the big bang theory. religion is supposed to consult

2:32 am

and conjoin, as well as explain. deism hardly counts as a religion. george washington would not kneel to pray. when his pastor rebuked him for setting a bad example, washington mended his ways. he stayed away from church on communion sundays. no ministers were present and no prayers were said when he died. washington had proclaimed that religion and morality are indispensable supports for political prosperity.

2:33 am

he said that "reason and experience both were best to expect that morality can prevail in exclusion for religious principles. the longer john adams lived, the shorter grew his creed. in the end, it was unitarianism. jefferson wrote those ringing words of the declaration, but jefferson was a utilitarian when he urged his nephew to inquire into the truth of christianity. "if it ends in a belief that there is no god, you'll find virtue in the comforts and pleasantness you feel in virtue's exercise."

2:34 am

james madison always explained away religion as an innate appetite. the mind, he said, prefers the idea of the self existing clause to an infinite series of cause and effect. even the founders who were unbelievers considered it a civic duty in public service to be observant unbelievers. two days after jefferson wrote his famous letter endorsing a wall of separation between church and state, he attended church services in the house of

2:35 am

representatives. services were also held at the treasury department. jefferson and other founders made statements like accommodations for the public's strong preference for religion to enjoy ample space in the public square. they understood that christianity fostered attitudes and aptitudes associated with useful to a popular government. protestantism emphasis on the individuals' direct relationship with god and the privacy of individual choice subverted convention hierarchical societies in which deference was expected from the

2:36 am

many towards the few. beyond that, the american founding owes much more to john locke than to jesus. rights that exist before government exists. rights that are natural and are not creations of the regime that exists to secure them. in 1786, the year before the constitution convention, it in the preamble for religious freedom, jefferson proclaimed "our civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions any more than our opinions and physics or geometry." since the founding, america's religious enthusiasm have waxed

2:37 am

and waned. the durability of america's denominations have confounded jefferson's prediction, which he made in 1822. he said there is not a young man now living in the united states who will not die a unitarian. he said his opponent was unfit to be president because, being a unitarian, he did not believe in the virgin birth. the public elected taft. there is a paradox at work. america is the first and most relentlessly modern nation. it is also the most religious

2:38 am

modern nation. one important reason for this is that we have disentangled religion from public institutions. there has long been a commonplace assumption, one that my dear friend called the liberal expectancy. it was, and still is, an assumption that pre-modern forces will lose their history. the two most important of these are religion and ethnicity. events refute the liberal expectancy.

2:39 am

religion still drives history. religion is also central to the emergence of america's public philosophy. at the risk of offending specialists by distortion through compression, what we offer a very brief placement of americans foundries. -- founders. machiavelli begins modern political philosophy. this spot is a convenient demarcation. the ancients sought to enlarge the likelihood of the emergence of noble leaders. machiavelli, however, took his

2:40 am

bearings from people as they are. he defined the political project as making the best of this flawed material. he knew that nothing would ever be made from the crooked timber of humanity. machiavelli was no democrat. he reoriented politics towards accommodations, strong and predictable forces rising from a great constant, human nature common to all people in all stations. for 44 years, machiavelli and luther were contemporaries. luther was no democrat.

2:41 am

in theory, and least of all in temperament. but he was a precursor. when summoned, he proclaimed, here i stand. i cannot do otherwise. he asserted the privacy of the individual and the individual's conscience. this expressed the logic of his political radicalism. without fully intending to do so, he celebrated individualism at the expense of tradition and of hierarchy.

2:42 am

because he was in humanity's past, and democracy was in humanity's future. the advent of maternity -- modernity coincided with a parallel development and a closely related field of philosophy, epistemology. the philosophy of knowledge, of how we know things. descate's played a role in reorienting the political fallout. -- political thought. he sought a ground of certainty, beyond revelation and beyond pure reason. he famously found such a ground in cognition itself. his formulation, cogito ergo sum. i think, therefore, i am.

2:43 am

then senses, sense-data. it was supplied the foundations for whatever certainties human beings can achieve. philosophy hobbe's that became the decisive. the bedrock of certainty came from his experience with religious warfare. this strife taught him that all human beings have one shared constant similarity. they all fear death. he directed a philosophy of despotism. in exchange for security, people would willingly surrender the precious sovereignty they possessed in the state of nature where life was solitary, brutish, and short. his philosophy, contained the

2:44 am

seeds of democracy. all human beings were equally under the sway of the narrative. all human beings can come up without the assistance of a priest, comprehend the basic passions that move the world. to the extent that the world of politics is driven by strong and steady passions and interests, to that extent, there will be a new science of politics. the science of politics based on what all human beings have in common, acknowledged supplied by the senses. because people do not agree about religious truths, and

2:45 am

because they fight over their disagreements, social tranquility is served by regarding religion as voluntary matter for private judgment. not state-supported and state enforced. in the interest of social peace, the higher aspirations of the ancient political philosophers were pushed to the margins of modern politics. those aspirations were considered, at best, unrealistic. at worst, downright dangerous. henceforth, politics would not be a sphere in which human nature is perfected. political project would not include appointing people towards their highest potentials. instead, a modern politics

2:46 am

would be based on the assumption that people will express and will act upon the strong impulses of their flawed nature's. people will be self interested. the ancients had asked, what is the highest of which mankind is capable? how can we pursue this in politics? hobbes asked, what is the worst that can happen in politics? and how can we avoid this? america's founders had a kind of political catechism that expressed modernity. what is the worst political outcome? tyranny. what a form of tyranny can

2:47 am

happen any republic governed by majority rule? tyranny of the majority. how could this be prevented? the answer is by not having majorities that can become tyrannical. reducing the likelihood the stable and tyrannical majority can emerge and endure. how was this to be achieved? by implementing james madison's revolution of democratic theory. of the diminutive madison, he was about 5 foot 3. never have there been such a high ratio of mind to mass. he was princeton's first graduate student and he turned

2:48 am

democratic theory upside-down. before madison, few political theorists believe democracy could be feasible only in a small face to face society. this was supposedly so because factions were considered the enemy of popular government small societies were thought to be least susceptible to the proliferation of factions. madison's revolutionary theory, the core of which is distilled in federalist paper number 10, was that a republic should be small but extensive, expand the scope of the republic in order to expand the number of factions. the more factions, the merrier. saving multiplicity of factions

2:49 am

will make it more probable that majorities will be unstable, shifting minority factions. madison related his clear-eyed and unsentimental view to the constitution's structure. the separation of powers. he also said ambition must be made to counteract ambition. >> that is the self- interestedness of rival institutions, presidents, legislatures will check one another. madison famously continued, it may be a reflection on human nature that such device should be necessary to control the abuses of government but what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature.

2:50 am

if men were angels no government would be necessary. if angels were to govern men, night external or internal controls on government would be necessary. so said madison, we must have a policy of supplying by opposite and rival interest that defect better motives. neither madison or the others were saying we should presuppose that america could prosper without there being a good motive somewhere. such motives are manifestation of good character. our sober founders were not so foolish as to suppose freedom contrive without appropriate education and other nourishments of character.

2:51 am

they understood this must mean education broadly understood to include not just schools, but all the institutions of civil society that explain freedom and equip citizens with the virtues freedom requires. these virtues includes self- control, modernization. these reinforce the rationality essential to human happiness. notice when madison like the founding father's generally spoke of human nature, he was not speaking as modern progressives do as manage inconstant, something evolving, something constantly formed and reformedly changing social and other historical forces. when people today speak of nature, they generally speak of flora and trees and animals and other things not human.

2:52 am

but the founders spoke of nature as a guide to and as a measure of human action. they thought of nature not as something merely to be manipulated for human convenience but rather as a source of norms to be discovered. they understood that natural rights could not be asserted, celebrated and defended unless nature, including human nature is regarded as a normative rather than a merely con ting nt -- contingent fact. this was a view but stressed by the view of teaching that nature is not chaos but rather as the replace of employment of chaos in the mind and will of the creator. this is the creator who endows us with natural right that is are inevitable, inalienable and

2:53 am

universal and hence the foundation of democratic quality. and these natural rights are the foundation of limited government. government defined by the limited goal of securing those rights so that individuals may flourish in their free and responsible exercise of those rights. a government thus limited is not in the business of imposing its opinions about what happiness or what excellence the citizens should choose to pursue. having such opinions is the business of other institutions, private and voluntary institutions, especially religious ones that supply the conditions of liberty. thus the founders did not

2:54 am

consider natural rights reasonable because religion affirmed them, rather the founders considered religion reasonable because it secured natural rights. there may, however, be a cultural contradiction. the contradiction is while religion can sustain liberty, liberty does not necessarily sustain religion. this is of paramount importance because of the importance of the declaration of independence. america's public philosophy is instilled in the declaration's second paragraph. we hold these truths to be self-evident. notice our nation was born with an assertion the important political truths are not merely knowable, they are self- evident, meaning they can be known by any mind, not clouded

2:55 am

by ignorance or superstition it is the declaration self-evident true that all men are created equal, equal not only in their access to the important political truths, but also in being endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights including life liberty and the pursuit of happiness. next comes perhaps the most important word in the declaration. it is the word secure. to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, jefferson wrote. primarygovernment's purpose is to secure preexisting rights. government does not create rights, it does not dispense them. here, concerning the opening paragraphs of the declaration is where wilson and modern

2:56 am

progressivism enter the american story. wilson urged people not to read what he called the preface to the declaration. he explicitly said if you wish to understand the real declaration of independence, do not read the preface. that is what everyone else calls the essence of the declaration of independence. wilson did so for the same reason he became the first president to criticize the american founding. and he did not criticize it about minor matters. he criticized it root and branch beginning with the doctrine of natural right which is he rejected. his criticism began there precisely because that doctrine dictates a limited government which he considered a cramped unscientific understanding of political seasons.

2:57 am

wilson disparaged the doctrine of natural rights as quote fourth of july sentiments." he did so because this doctrine limited the plan to make government more scientific in the service of a politics that is much for ambitious. wilson's formative years were the years in which darwin's theory of evolution seeped into the social science, including political science. wilson the first president of the american political science association wanted the political project to make government evolve as human nature evolves. only by doing so he thought could government help human nature progress. this is why for progressives

2:58 am

progress meant progressing up from the founders and they are falls because static understanding of human nature. only government unleashed from the confining doctrine of natural rights could be muscular enough for this project. such a government needed not the founder's static constitution but a living constitution. a much more permissive constitution, that is the new progressive government needed the old constitution to be construed as granting to the government, powers sufficient for whatever projects the government decided or required for progress. what then about the framer's purpose of writing a constitution to protect people from popular passions.

2:59 am

wilson argued that the evolution of society had advanced so far that such worries were acknist i can. -- anachronistic. the passions in society such as the united states had wilson believed been domesticated. they no longer threatened to be tyrannical or threatened the social order. hence wilson thought the state emancipated from the founders static constitution should be and i quote him an instrumentality for quickening in every way both collective and individual development. well, who was to determine what ways might not be suitable. the answer must be the

3:00 am

government itself. wilson was as progressives tended to be a his or the cyst, -- a historicist. that is someone with a strong sense of theology, history he thought had its own unfolding logic, it's autonomous trajectory, it's proper destination. it was the duty of leaders to discern the destination towards which history was progressing and to make government the unfettered better of this progress.

194 Views

IN COLLECTIONS

CSPAN Television Archive

Television Archive  Television Archive News Search Service

Television Archive News Search Service

Uploaded by TV Archive on

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11